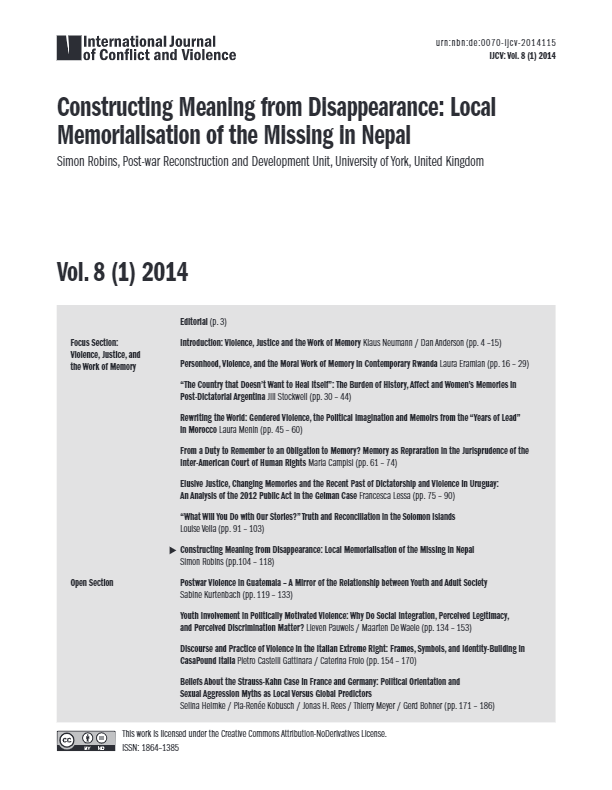

Constructing Meaning from Disappearance: Local Memorialisation of the Missing in Nepal

Disappearance in conflict creates challenges of identity and meaning for the families of those whose fate remains unknown: women, for example, who do not know if they are wives or widows and desperately seek to construct positive meanings from their experience. This empirical study of the families of those disappeared during Nepal’s Maoist insurgency focuses on processes of local memorialisation and post-conflict politics of memory in rural areas and on how and why victims seek certain forms of recognition and memorialisation, including their psychosocial motivations. The means of memorialisation chosen by families of the missing served to confirm in a highly social way that the disappeared are missing not dead, and sought to integrate stigmatised families into communities from which they had been alienated by violations. Memorialisation can strengthen the resilience of families of the missing; as a social process, it addresses both the emotional and the social impacts of disappearance. Remembering the disappeared in ways that can aid the well-being of the families left behind demands local approaches that are contextualised in the cultural and social worlds of impacted communities: this challenges memorialisation, and transitional justice processes more broadly, that emerge exclusively from institutional processes directed by elites.