International Day of the Disappeared: Memory Portraits in Peru

Many families in Peru lost loved ones during the period of violence that tore the country apart at the end of the 20th century. An art project is putting faces to the names of those who went missing.

Between 1980 and 2000, Peru was racked by violence as armed groups clashed with the Peruvian state. Civilians were caught in the middle and became victims of terrorist acts and human rights violations, perpetrated by both sides.

According to the Unified Victims Registry (RUV), the conflict affected “229,000 civilian, police and military individuals, 5,712 communities, and 159 organizations of displaced people”. As of January 2022, the National Registry of Missing Persons and Burial Sites (RENADE) had documented 21,647 cases of missing people, of which only 1,858 had been successfully resolved.

In 2001, despite the ongoing instability in Peru, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (CVR) was established. It was tasked with investigating crimes committed during the internal armed conflict. Several years later, the High-Level Multisectoral Commission for Reparations (CMAN) was founded. With the support of these institutions, in 2016 Jesús Cossio, Alejandro Olazo and Illari Orccottoma set up Memory Portraits, an artistic and social project that aims to reconstruct portraits of missing people for their families to remember them by.

Jesús Cossio is an illustrator and has spent several years creating graphic novels based on real cases of the armed violence in Peru between 1980 and 2000. With the CMAN, he has led workshops for children from areas affected by violence. Alejandro Olazo has been working as a photographer for ten years, focusing on documenting the post-conflict process in Peru. He has dedicated nearly seven years to the search for missing people. Illari Orccottoma is an audiovisual producer who works in film production. She has provided logistical support and advice on how to develop the project and plays a key role in designing workflow and raising awareness of the work the team produces.

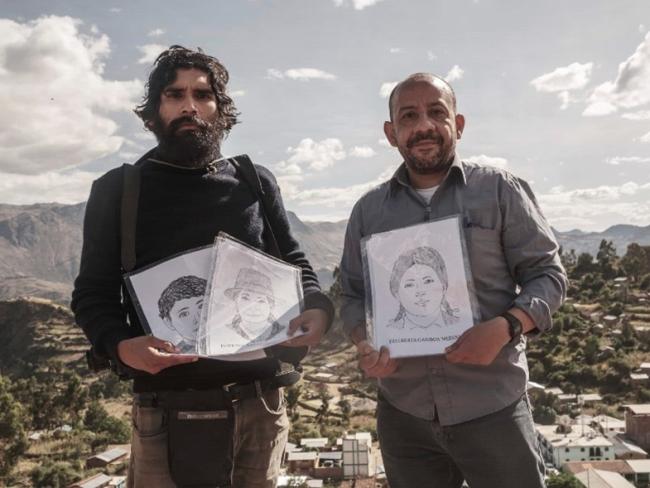

Many families in Peru have no photo or image of their missing loved ones. The initial concept behind the project was, therefore, to provide an image for these families. In Peru, family members often gather outside a court where hearings are taking place to find out what happened to their loved ones. The pictures provide a symbolic form of healing and help to fill the hole left in people’s lives. Later, the scope of the project was expanded to include other situations in which such images could be displayed, such as burials.

In 2002, for instance, the team completed a number of portraits to be displayed during the burial of 69 residents of Accomarca, a town in the Ayacucho region. They had been burned alive in a house in 1985. According to the CVR’s final report, most victims of violence were from this region and spoke Quechua as their first language. There are very few records of these people, and any that do exist are often basic. It is left to their families to document their stories, as from an official government perspective these people are deemed not to exist at all. So, the portraits are immensely significant for the family members who receive them.

To create a portrait, the team interviews the relatives – sometimes three or four times – to hear memories and anecdotes about their loved ones. The relatives have to be closely related to the missing person, as the first stage involves identifying physical resemblances between the two – similarities in the eyes, nose, cheekbones, overall facial structure and even skin colour. These details give Jesús a starting point from which to build the portrait. Meanwhile, Alejandro creates a photographic representation based on physical descriptions from the relative. Using these physical characteristics and drawing on the memories shared during the interview, Jesús produces an initial sketch. Alejandro then takes profile photos and half-length shots of each relative to help capture finer details. To minimize emotional distress and avoid causing any further trauma, the interviews are short and informal. They remained focused on drawing out all the elements essential for the portrait.

The Memory Portraits project has since created portraits with the support of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in the Ayacucho region. The focus was on the Oronccoy community to coincide with the state’s scheduled delivery of the remains of missing people in early July 2023. The event brought together relatives from all over the country who wished to give their loved ones a dignified burial. There are further plans to create portraits in the jungle region of Satipo.